HOW BRAZING WORKS.

A brazed joint is made in a completely different way from a welded joint.

The first big difference is in temperature. Brazing doesn’t melt the base metals. So brazing temperatures are invariably lower than the melting points of the base metals. And, of course, always significantly lower than welding temperatures for the same base metals.

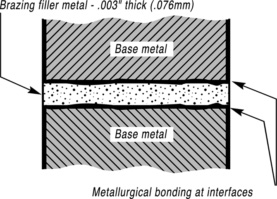

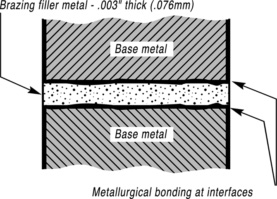

If brazing doesn’t fuse the base metals, how does it join them? It joins them by creating a metallurgical bond between the filler metal and the surfaces of the two metals being joined.

The principle by which the filler metal is drawn through the joint to create this bond is capillary action. In a brazing operation, you apply heat broadly to the base metals. The filler metal is then brought into contact with the heated parts. It is melted instantly by the heat in the base metals and drawn by capillary action completely through the joint.

This, in essence, is how a brazed joint is made.

What are the advantages of a joint made this way?

WHY CHOOSE BRAZING

First, a brazed joint is a strong joint. A properly-made brazed joint (like a welded joint) will in many cases be as strong or stronger than the metals being joined. Second, the joint is made at relatively low temperatures. Brazing temperatures generally range from about 1150°F to 1600°F (620°C to 870°C).

Most significant, the base metals are never melted.

Since the base metals are not melted, they can typically retain most of their physical properties. And this “integrity” of the base metals is characteristic of all brazed joints, of thin section as well as thick-section joints. Also, the lower heat minimizes any danger of metal distortion or warping.

(Consider too, that lower temperatures need less heat which can be a significant cost-saving factor.)

An important advantage of brazing is the ease with which it joins dissimilar metals. If you don’t have to melt the base metals to join them, it doesn’t matter if they have widely different melting points. You can braze steel to copper as easily as steel to steel.

Welding is a different story. You must melt the base metals to fuse them. So if you try to weld copper (melting point 1981°F/1083°C) to steel (melting point 2500°F/1370°C), you have to employ rather sophisticated, and expensive, welding techniques.

The total ease of joining dissimilar metals through conventional brazing procedures means you can select whatever metals are best suited to the function of the assembly—knowing you’ll have no problem joining them no matter how widely they vary in melting temperatures.

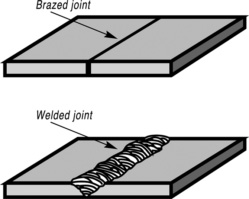

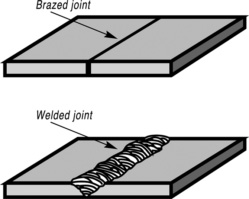

Another advantage of a brazed joint is its good appearance. The comparison between the tiny, neat fillet of a brazed joint and the thick, irregular bead of a welded joint is like night and day.

This characteristic is especially important for joints on consumer products, where appearance is critical. A brazed joint can almost always be used as is, without any finishing operations needed. And that too is a money-saver.

Brazing offers another significant advantage over welding in that brazing skills can usually be acquired faster than welding skills. The reason lies in the inherent difference between the two processes. A linear welded joint has to be traced with precise synchronization of heat application and deposition of filler metal. A brazed joint, on the other hand, tends to “make itself” through capillary action. (A considerable portion of the skill involved in brazing actually lies in the design and engineering of the joint.) The comparative quickness with which a brazing operator may be trained to a high degree of skill is an important cost consideration.

Finally, brazing is relatively easy to automate. The characteristics of the brazing process—broad heat applications and ease of positioning of filler metal—help eliminate the potential for problems. There are so many ways to get heat to the joint automatically, so many forms of brazing filler metal and so many ways to deposit them, that a brazing operation can easily be automated to the extent needed for almost any level of production.

sales@welding-material.com

sales@welding-material.com